Kiswahili is spoken across eastern and central Africa. Mother-tongue speakers are found mainly along the coast, but Kiswahili is spoken as a second or third language by people around the world. According to Unesco, which in 2021 proclaimed 7 July as World Kiswahili Language Day, it’s spoken by 200 million people.

What led to it becoming so prominent?

Kiswahili’s role as a prominent symbolic and practical language in Africa is the result of multiple factors. These range from political and economic to cultural and historical. Already by the 1800s Kiswahili was being used all along the caravan trade network that crisscrossed east-central Africa. In the centuries before this, the language had been used to formulate legal, philosophical and poetic contributions that influenced the entire Indian Ocean world.

But one of the arguments of my book is that the creation of a standardised version of the language resulted by the mid-1900s in a version of Kiswahili that was more portable than ever before. A standard language is a uniform written version that is generally recognised as the “official” form. This comes with the creation of dictionaries, grammars and literature that allow this version to travel further.

Another important part of the story of the standardisation of Kiswahili is that it was central to a variety of community-building projects across the course of a century. It was used by formerly enslaved students and missionaries alongside native speakers on Zanzibar and was central as a language of administration in Tanganyika, Zanzibar, Kenya and parts of Uganda during the colonial period. Kiswahili also played a political role in the anti-colonial movements of eastern Africa and among southern African freedom fighters who trained in Tanzania in the 1960s and 1970s. It was even embraced by some US civil rights activists.

All these communities used the language at various times to strengthen ties and communicate across barriers that otherwise might have kept people apart. This led not only to an increase in the number of people speaking and writing Kiswahili, but also to its reputation as a potential pan-African and even global connecting language.

Many, including literary heavyweights Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o from Kenya and Wole Soyinka from Nigeria, have advocated for the embracing of Kiswahili as a pan-African language of communication.

But there’s legitimate concern that the expanded use of Kiswahili in official and unofficial realms could endanger the linguistic diversity of east Africa.

It’s a problem for which I don’t have an answer. Perhaps multilingualism is the key. As Ngũgĩ encouraged in a 2021 speech in Mombasa:

Therefore let us be proud of our mother tongues; let us be proud of Kiswahili as the national language; and on top of that let us add the knowledge of English or Mandarin or French or Yoruba, etcetera. These will only give strength to our proficiency and communication. But our foundation is made of our mother tongues and the language of the entire nation, that is Kiswahili.

What exactly is standardised Kiswahili?

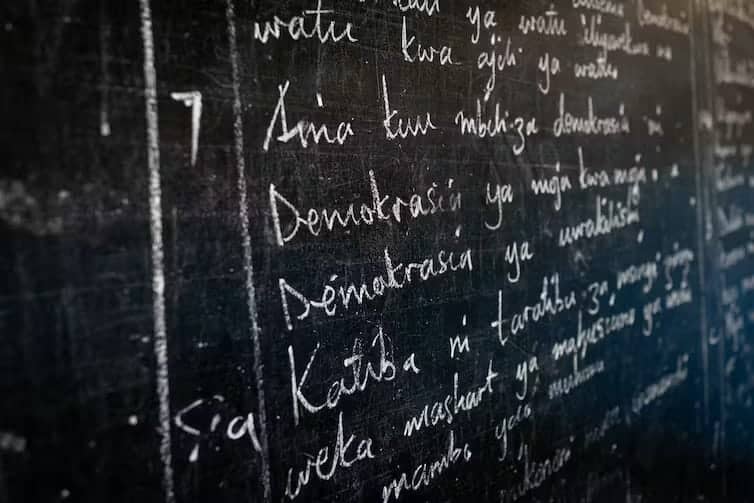

Just as there are many “Englishes” spoken around the world, so are there multiple “Kiswahilis”. That’s to say, Kiswahili is a language of multiple dialects – the Kimvita spoken at Mombasa, for instance, or the Kiamu of Lamu – of which Standard Swahili is just one. It is the version that shapes the textbooks and curricula with which Kiswahili is taught around the world, so that most students learning Kiswahili in classrooms are learning Standard Swahili.

Its history is a long one that did not follow a single, straight path. However, broadly speaking, Standard Swahili is based on Kiunguja, the Zanzibari dialect of the language. It’s also important to note that while Standard Swahili is written in the Latin script – the alphabet used to write English, French, Italian etcetera – Kiswahili has a much longer history of being written in the Arabic script, a tradition that lives on in some communities.

What were the key moments in the standardisation of the language?

One of my main arguments is that the standardisation of Kiswahili was a long-term and, by necessity, collaborative process. The standard version was neither wholly imposed by the British colonial regime in the 1920s, nor was it a “naturally” developed tool of anti-colonial resistance. Starting in 1864 with the arrival of Anglican missionaries on Zanzibar, through the independence and early post-colonial eras, multiple communities participated in the process. They all used the language to create their own diverse communities.

One of my favourite examples to describe this process is the figure of Owen Makanyassa. He was enslaved as a young man, but before arriving at its destination the ship carrying him was captured by the British Royal Navy and, in the late 1860s or early 1870s, Makanyassa was placed under the care of a missionary society on Zanzibar. He attended the mission’s school and became an invaluable worker at its printing press, producing some of the translations that would go on to form the basis of Standard Swahili. Though Makanyassa and his fellow students and workers spoke a variety of mother tongues, their language of communication very quickly became Kiswahili, and they all participated in this early stage of its standardisation – though they haven’t always been credited for their contributions.

In my book I zoom in on moments like this, moments in which freedom and unfreedom, oppression and empowerment, official and unofficial knowledge production combined, slowly creating a written version of Swahili that would be exported around the world, creating a truly global language.

Download a free copy of the book at Ohio University Press

Morgan J. Robinson, Assistant Professor, Mississippi State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.